The daily use of a pill such as Truvada has been a mainstay of the fight against HIV infections for over a decade. This kind of preventive medication, called pre-exposure prophylaxis, or PrEP, has demonstrated impressive efficacy in clinical trials, with up to 99% success rate in preventing new HIV infections that are contracted through sexual contact; however, translating this clinical success to real-world situations has proven difficult because daily medication regimen adherence can be irregular.

Many people may not regularly take their prescription PrEP drugs in real-world conditions. According to a South African study, women frequently felt that using the pill was stigmatized. They were afraid that if they were taking PrEP, their sexual partners would think they were taking it because they were already HIV positive or because they were seeing other people.

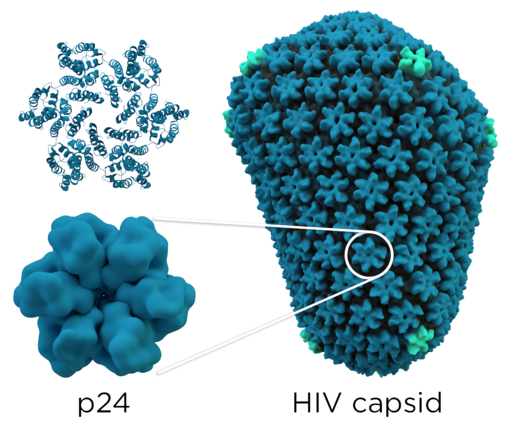

A novel experiment dubbed PURPOSE 1 has surfaced in response to these adherence issues, providing a potentially effective substitute for daily PrEP pills: a twice-yearly injection of the medication lenacapavir. This experiment marks a major development in HIV prevention measures and is sponsored by the California-based pharmaceutical business Gilead Sciences.

A double-blind, randomized study with 5,300 cisgender women from South Africa and Uganda is called the PURPOSE 1 trial. Out of these individuals, 2,134 underwent an injection of lenacapavir, while the remaining individuals were administered one of two kinds of daily PrEP pills. August 2021 marked the start of the experiment, and the preliminary findings are encouraging. None of the female recipients of the lenacapavir injection had developed HIV as of yet. On the other hand, about 2% of people who received the oral PrEP options—Descovy or Truvada—have tested positive for HIV. This infection incidence is consistent with infection rates found in other oral PrEP clinical trials.

The Data Monitoring Committee, an impartial group of specialists entrusted with monitoring the advancement of clinical trials, suggested that Gilead terminate the trial’s blinded phase and provide lenacapavir to every research subject due to the importance of these results. Gilead made these findings public on June 20 and gave each participant the option to get the lenacapavir injection.

The HIV data for sub-Saharan Africa inform the study’s focus on women in that region. Despite making up only 10% of the world’s population, sub-Saharan Africa is home to two-thirds of all HIV-positive people worldwide, with 25.7 million of the 38.4 million people living with HIV living in this region. In addition, about 4,000 African teenage girls and young women contract HIV for the first time every week.

The response to these trial results has been overwhelmingly positive in the early going. The trial hasn’t been subjected to peer review yet, but the early results have excited a lot of people in the medical field. Dr. Jason Zucker, an infectious disease specialist and assistant professor of medicine at Columbia University’s Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons, shared his excitement by saying, “It’s amazing. Taking a medication every day is difficult. There is a great deal of promise for a drug that is administered every six months.”

This opinion was mirrored by Dr. Philip Grant, clinical associate professor and head of the HIV clinic at Stanford University School of Medicine, who pointed out that lenacapavir could fill in important gaps in preventative alternatives for populations that struggle with adherence. He underlined the possible advantages of injectable PrEP, especially for people who have trouble adhering to regular drug schedules.

The efficacy of oral PrEP varies greatly in real-world situations, even with the high efficacy rates seen in clinical trials. For instance, a study discovered that the efficiency of PrEP may be as low as 26% in some groups, such as men under 30. In order to emphasize the significance of adherence, Dr. Zucker said, “Medications work when you take them. There is a lot of potential for a medicine that is administered every six months since, in essence, you are protected for a full year if you can make two visits annually.”

As a new PrEP alternative, advocacy groups have also stated that they favor lenacapavir. In a statement, the People’s Medicines Alliance, an international alliance including more than 100 organizations from 33 countries, referred to lenacapavir as “a real game-changer,” particularly for those who are subjected to stigma and discrimination in low- and middle-income nations.

Although lenacapavir has been approved by the FDA in the US since 2022 for the treatment of HIV that is resistant to multiple drugs, its use as a prophylactic measure is new. The first clinical trial testing lenacapavir for HIV prophylaxis is the PURPOSE 1 trial.

The global south is trying to improve HIV prevention, and the PURPOSE 1 experiment is a part of that effort. It is one of many ongoing research projects that support the group’s goal of ending the HIV epidemic by 2030. Lenacapavir’s effectiveness is being assessed in PURPOSE 2, a continuing experiment that includes cisgender men, transgender men, transgender women, and non-binary people who have sex with partners who were assigned male at birth. Several nations, including South Africa, Thailand, Argentina, Brazil, Mexico, Peru, and the United States, are participating in this experiment.

Lenacapavir’s possible approval and broad usage for HIV prophylaxis will not be without difficulties, mostly related to cost. According to a study presented at the 24th International AIDS Conference (AIDS 2022), PrEP pills should cost less than $54 per patient annually for nations such as South Africa to afford. On the other hand, in 2023, the annual cost of lenacapavir as an HIV medication for new patients in the US was $42,250. In contrast, oral PrEP options may be obtained for less than $4 a month.

Dr. Grant stressed that access to these drugs, rather than their availability, is the main obstacle to HIV prevention. Protesters in South Africa and Uganda have urged Gilead Sciences to grant a license for lenacapavir to the Medicines Patent Pool, an entity supported by the UN that makes it easier to produce generic copies of drugs. This would enable the production of reasonably priced generic lenacapavir.

Using cabotegravir, an injectable PrEP drug with an extended half-life produced by ViiV Healthcare, as an example, these activists express concern about possible delays in the release of generic equivalents. Despite being more effective than oral alternatives and receiving FDA approval in 2021, generic versions of cabotegravir are currently awaiting examination by the World Health Organization to verify their efficacy. Therefore, it’s doubtful that generic cabotegravir will be accessible in Africa until 2027.

Owing to lenacapavir’s early success, Gilead has pledged, subject to approval, to provide the medication to high-incidence, resource-constrained nations quickly, sustainably, and in adequate amounts. In order to facilitate the creation of generic versions prior to the original patent’s expiration, their access approach involves the creation of a voluntary licensing program. Vice president of HIV Clinical Development at Gilead, Dr. Jared Baeten, stated that the availability schedule will be contingent upon the results of additional trials and the approval and regulatory review procedures.

Dr. Zucker emphasized the significance of resolving financial constraints and expressed optimism that steps will be taken to lessen barriers to obtaining lenacapavir. Lenacapavir has the potential to revolutionize HIV prevention tactics, but its effectiveness will depend on how easily and reasonably available it is.

Leave a Reply