On Tuesday, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) declared the commencement of two noteworthy clinical trials that are intended to assess the efficacy and safety of an HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) medication among marginalized demographic groups. This effort, which focuses on groups like women and intravenous drug users that have previously been underrepresented in clinical studies, represents a crucial first step in resolving the inequities in HIV research and treatment.

The goal of these new trials is to collect detailed information about the twice-yearly administration of lenacapavir, an HIV preventative medication. The medicine, which aims to stop HIV from spreading, will be thoroughly researched in cisgender women—those who were assigned the gender “female” at birth—as well as injectable drug users. Federal figures show that women and intravenous drug users accounted for 18% and 7% of new HIV diagnoses in the United States in 2021, respectively, underscoring the significance of this research. In addition to these categories, key demographics that have not received enough attention in the context of HIV research include Black, transgender, and pregnant people.

The primary objectives of these NIH studies are to assess the pharmacokinetics, acceptability, and safety of lenacapavir. Understanding pharmacokinetics—the study of how a drug flows through the body over time—is crucial to understanding the medication’s long-term safety and effectiveness. An injectable antiretroviral drug might offer a less rigorous regimen for people at risk of HIV. Every six months, it will be administered.

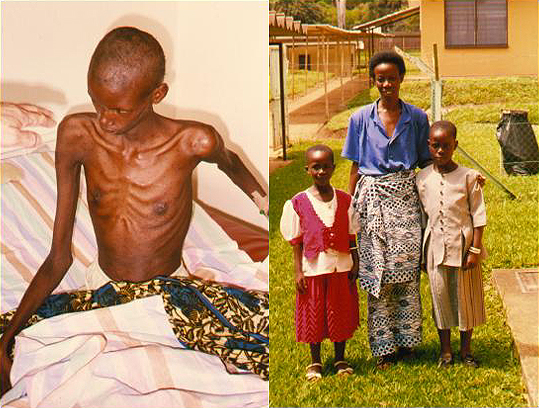

According to HIV.gov, over a million Americans are living with HIV at the moment, and roughly 13% are not aware of their status and require testing. The Biden administration published a strategic plan in December 2021 with the goal of ending the HIV/AIDS epidemic in the United States by 2030, realizing the urgency of the situation. This approach is in line with global trends as documented by UNAIDS, which shows that the number of people receiving antiretroviral medication increased significantly from 7.7 million in 2010 to 29.8 million in 2022.

Nevertheless, there are still difficulties. According to a new study conducted by the CUNY Graduate School of Public Health and Health Policy in New York City, a significant percentage of people who start PrEP eventually stop using it. This is a worrying trend. This emphasizes how important it is to continue supporting and conducting research in order to maintain continuous adherence to HIV prevention methods.

Reaching the most impacted groups with HIV is crucial, as highlighted by Health and Human Services Secretary Xavier Becerra, who said, “We need to reach people living with the virus where they are in order to end the HIV epidemic, and this program allows us to do just that.” This declaration was made in response to the Department of Health and Human Services’ announcement of an increase in funding of $147 million to support HIV/AIDS initiatives.

With regard to treatment-experienced patients with multidrug-resistant HIV who have not responded to other treatments because of resistance, intolerance, or safety concerns, lenacapavir has already been approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for use in combination with other antiretroviral therapies. To investigate its potential as a preventive intervention, this proven safety profile is the first step.

Given their increased vulnerability and historically poor representation in clinical research, Black and/or Latina women will be given special attention when enrolling in the first of the NIH trials, with a focus on cisgender women in particular. Those who inject drugs are another population heavily affected by HIV but frequently disregarded in preventive research; the second experiment seeks to enlist a wide cohort of these people.

Gilead Sciences is sponsoring and funding these NIH-supported trials, which will be carried out via the HIV Prevention Trials Network. Numerous NIH institutions, such as the National Institute on Drug Abuse and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, support this network, underscoring the coordinated effort to approach HIV prevention holistically.

2020 study has shown that lenacapavir has promising outcomes. In a small sample of individuals, a single injection of the medication was proven to lower blood levels of HIV and to keep active levels in the bloodstream for more than six months. Lenacapavir was shown to be safe and to be active in the body for a considerable amount of time in a study involving forty healthy participants. Furthermore, a single injection of Lenacapavir effectively decreased viral levels in 32 untreated HIV positive persons in a matter of nine days.

Increased access of PrEP is something that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has long argued is essential to ending HIV/AIDS in the United States. The CDC has noted hopeful developments as PrEP becomes more widely available and more reasonably priced, especially for younger populations. HIV infections among people in the 13–24 age range fell by 34%, from 9,300 infections per year in 2017 to 6,100 infections in 2021.

With the execution of these critical clinical studies, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) has demonstrated its commitment to advancing inclusive research, which is a significant advancement in the ongoing battle against the HIV epidemic. This dedication highlights a paradigm-shifting methodology in health research by emphasizing the participation of historically underrepresented and diverse populations, which have frequently been disregarded in earlier investigations. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) seeks to address and correct the gaps in HIV prevention and treatment results by focusing on underrepresented populations, including cisgender women, Black and Latina individuals, and injectable drug users.

Furthermore, the NIH’s innovative approach is demonstrated by the well-planned application of state-of-the-art treatment choices, such as the novel medication Lenacapavir. The antiviral drug lenacapavir, which is taken every two years, is a major development in HIV prevention technology. The standard of care for people at risk of HIV infection could be completely changed by its potential to provide a more feasible and effective prophylactic regimen, especially in communities where access to healthcare services has historically been hampered and new diagnoses are more common.

These clinical studies’ extensive efforts are expected to produce priceless data that will improve our comprehension of how HIV prevention tactics can be tailored to the needs of various population groups. This research is essential to attaining health equity in addition to being about the creation and testing of a novel medication. The goal of the NIH is to make sure that everyone may benefit from medical discoveries by including people with different backgrounds and risk factors in a systematic way. This will help to create a more equitable and inclusive healthcare system.

These trials could have an impact that goes beyond only lowering the risk of HIV transmission. It is a part of a larger campaign to eliminate the structural injustices that have long hampered medical research and healthcare provision. Setting a new benchmark for public health programs, the NIH prioritizes diversity while utilizing scientific innovation. These initiatives have the potential to significantly advance the ultimate objectives of ending the HIV epidemic and creating a healthcare system in which every person can access the treatment and prevention they require, irrespective of their circumstances or background.

All things considered, the NIH’s program is proof of the organization’s steadfast dedication to approaching the complexity of the HIV epidemic from an equitable and innovative standpoint. The use of cutting-edge therapy options like Lenacapavir, along with the participation of underrepresented populations in these clinical studies, highlights a comprehensive and proactive approach to public health. This comprehensive approach has the potential to not only further scientific understanding but also pave the path for a time when HIV will not be a threat to public health and universal access to healthcare will be a reality.

Leave a Reply