In comparison to the traditional MRI method, a new tracing agent for PET/CT imaging provides better accuracy in determining the extent of prostate cancer, as shown by a recent study by researchers at the University of Alberta. This is especially true for intermediate- and high-risk cases. This ground-breaking study, which highlights the important developments in prostate cancer diagnostic imaging, was published in the journal JAMA Oncology.

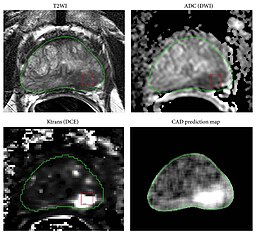

Findings from the study demonstrated that the new PET/CT imaging technique correctly identified the location and margin of tumors in 45% of cases, which is almost twice as accurate as the 28% accuracy rate obtained by MRI. The relevance of these discoveries was emphasized by Adam Kinnaird, who holds the Frank and Carla Sojonky Chair in Prostate Cancer Research and is also an assistant professor of surgery and adjunct assistant professor of oncology. Many treatment decisions are made depending on the precise location of the cancer within the prostate, according to Kinnaird. In cases where a patient is undergoing prostate excision and the disease has spread to other parts of the body, we must extend our treatment margins to ensure that no harmful tissue is abandoned. In a manner similar to this, a radiation oncologist may decide to improve disease management by directing radiation therapy into the center of the cancer. Thanks to this new imaging test, we can now precisely identify the areas that require therapy.

The novel imaging procedure entails the injection of 18F-PSMA-1007, a radioactive tracer specific to prostate tumors. After being injected into the patient’s bloodstream, this tracer is monitored with a combination of computed tomography (CT) and positron-emitting tomography (PET). Not as much progress has been made in the past using different tracing agents to increase the utility of PET/CT images.

In the study, 134 men from Alberta who were scheduled for radical prostatectomy—a surgical procedure that involves removing the prostate gland, surrounding tissues, and neighboring lymph nodes—had both PET/CT and MRI scans done within a two-week period. The precision of the imaging tests was then contrasted with the precise position and size of the tumors discovered during surgery by the researchers.

The clinical trial’s wider significance for world medicine were underlined by Kinnaird, who predicted that PET/CT scans with the new tracer would soon overtake other methods as the gold standard for diagnosing prostate cancer. None of the research subjects had any negative effects, even though the test only entailed a minor amount of radiation exposure. According to Kinnaird’s prediction, patients with prostate cancer may no longer need to undergo further CT and bone scans, which would result in fewer hospital visits, shorter turnaround times for results, and lower radiation exposure.

Patrick Albers, a co-author of the paper and graduate research fellow, emphasized the potential advantages of the novel imaging test, notably in minimizing the need for several diagnostic procedures. Since these scans are only available in Edmonton or Calgary, it will be quite exciting if you can replace three tests with one test and obtain more accurate information, according to Albers.

Another clinical trial headed by Kinnaird has already been started as a result of the trial’s encouraging outcomes. This trial aims to find out if the PET/CT scan can be used to guide ablation, a process that employs energy—such as heat, cold, or electricity—to remove cancer cells within the prostate.

While Health Canada approves the new imaging agent, it is presently only available at a few treatment sites nationwide. However, in the interim, the Alberta government has set up $3 million to give 2,000 men access to these new scans.

In a related development, Kinnaird’s research team conducted a second study that examined the prognosis of Black males with prostate cancer. The study, which was published in JAMA Network Open, examined data from the Kinnaird-chaired Alberta Prostate Cancer Research Initiative (APCaRI). 177 of the 6,534 males in the research who received a prostate cancer diagnosis between 2014 and 2023 self-identified as Black. The results revealed that although Black men were diagnosed two years earlier on average at age 64 as opposed to age 66 for other males, they had metastasis-free rates and survival rates comparable to the overall patient population. Rather than waiting until age 50 as is currently recommended, Kinnaird suggested that Black men be offered routine screening beginning at age 45.

According to Kinnaird, men of African and Caribbean origin had a twice as high lifetime risk of prostate cancer as those of Caucasian heritage, with research from the United States and the United Kingdom indicating a possible biological foundation for this difference. The Alberta results, which come from a publicly funded healthcare system, suggest that socioeconomic factors like racism, poverty, and limited access to healthcare may be more important than genetics. Kinnaird, however, brought up the point that these countries have two-tier or mostly private healthcare systems.

For men of African descent and other high-risk groups, both the American Urology Association and the European Urology Association advocate earlier screening; however, Canadian standards do not presently follow this practice. In light of the new information, Kinnaird stated that he hoped these rules will be revised.

He also cited earlier studies showing notable differences in prostate cancer outcomes and testing among Indigenous males. Kinnaird claims that compared to men in other communities, Indigenous men undergo less prostate cancer testing. This difference is probably caused by a lack of access to healthcare, especially in rural and remote locations. Insufficient testing results in diagnosis at a later stage, when there are fewer effective treatment options and a higher risk of the illness being deadly.

Kinnaird emphasized how crucial early detection is to enhancing the prognosis for prostate cancer. He said, “We have a cure rate of 95% or higher if we can detect prostate cancer at an early, localized, and treatable stage.” On the other hand, cancer becomes a fatal illness for which there is no treatment if it is discovered too late and has spread. The substantial disparity between the results of early and late detection highlights the critical need for proactive screening initiatives and fair access to healthcare.

The research carried out by Kinnaird and his colleagues highlights the significance of developments in early screening and diagnostic imaging. These developments are crucial for enhancing healthcare outcomes for all men, especially those in underprivileged and high-risk communities. They go beyond simple technology innovations. Prognosis and survival rates can be improved and treatment choices much improved by early and reliable detection techniques, such as the recently developed PET/CT imaging test.

These findings also highlight how important it is to address healthcare inequities that impact marginalized populations, such Indigenous men. Prostate cancer is most treatable when detected in its early stages, which can be achieved by healthcare practitioners by making sure these groups receive timely and sufficient testing. This strategy can assist in closing the disparity in healthcare results and offering more equitable care to every person, irrespective of their location or socioeconomic background.

In summary, Kinnaird’s research highlights the critical role that advances in diagnostic imaging and early screening play in the fight against prostate cancer. These initiatives seek to increase the precision of diagnoses, strengthen treatment regimens, and ultimately save lives, especially in high-risk and marginalized communities that have traditionally encountered obstacles to receiving quality healthcare.

Leave a Reply